From Peru, With Love

Peru.

On this land once walked one of the most impressive civilizations known to mankind. The remnants of temples and homes still decorate the mountainsides, standing as stone reminders of a history long passed. And on the flatter plains of Nazca, mysterious markings sprawl out for miles, their shapes only becoming clear when seen from above. A hummingbird, a monkey, a mosquito, these are the marks that man has made for a purpose long forgotten now.

While the Pacific Ocean laps constant as ever, still providing fish on which local diets rely, time has wound forward and the dense city of Lima has developed into a metropolitan destination for tourists and modern businesses.

Open-air restaurants serve spicy, cool ceviche that leaves a citrus tang on the tongue. Coffee here is strong and abundant. And in the more rural areas, simple dishes of potatoes or corn meal are the norm. It’s a rich cuisine that largely reflects the distance from the lake or sea.

Mountain towns fix comfort foods to warm the belly when the winds and altitude can be taxing on spirits, while coastal towns have lighter meals for when the days are hot and humid, seemingly never relieved by rain. Rain is so infrequent, in fact, that the government sends trucks to water the trees that decorate their urban space.

Makers travel to big cities like Lima from the far reaches of rural mountains in the hopes of finding work. But their travels away from their hometowns are often to no avail, and they arrive to find that the jobs in the city are already filled.

The polished district of Miraflores expands outward, away from the ocean, and as the hills ascend, the houses become poorer, and the streets become crowded. The ornate museums and official buildings seem so far away.

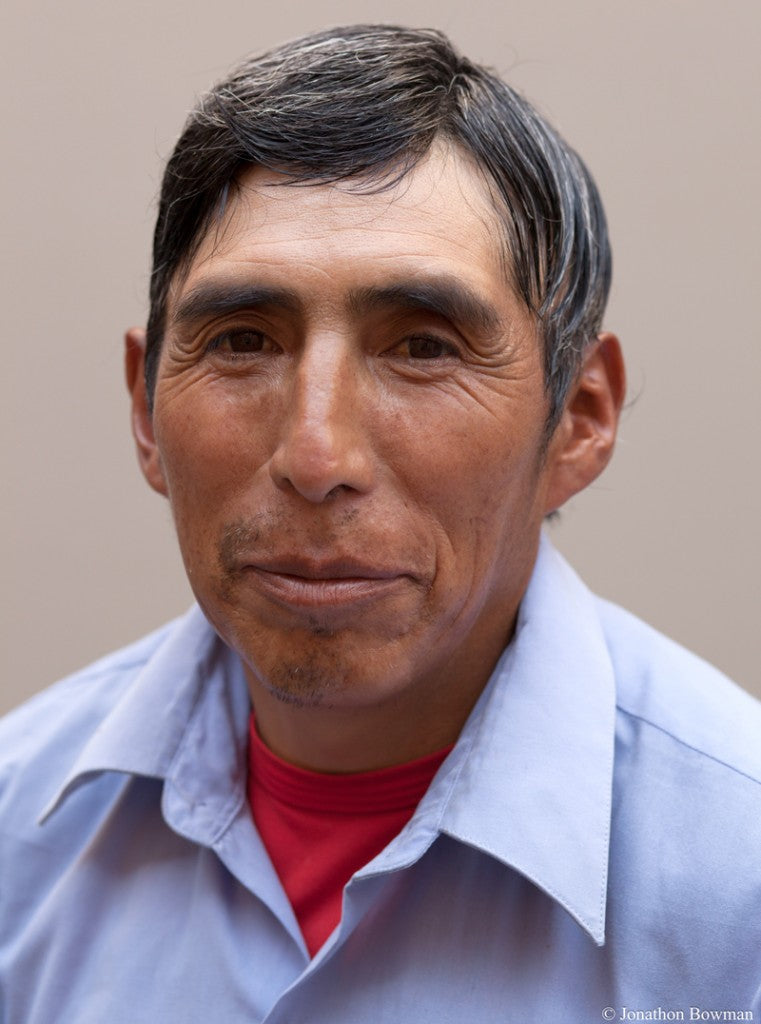

Four hours to the north, lies Santa Barbara: a small village near the city of Huancavelica. This was the hometown of Celestino Hilario. After the death of his mother when he was a teenager, he left school so that he could help his father run their cattle farm. “There was only cattle because nothing grew there, not even potatoes,” he recalls. The barren land was a challenge to the family, but it was political violence that eventually forced them to leave.

Four hours to the north, lies Santa Barbara: a small village near the city of Huancavelica. This was the hometown of Celestino Hilario. After the death of his mother when he was a teenager, he left school so that he could help his father run their cattle farm. “There was only cattle because nothing grew there, not even potatoes,” he recalls. The barren land was a challenge to the family, but it was political violence that eventually forced them to leave.

“They killed my brother-in-law, a cousin and a nephew; two other brothers-in-law went missing and another was put in jail. Three of my sisters are widows.” He had no choice but to take his wife and small daughter away from the village, and resettle closer to Huancavelica.

“Many persons in Santa Barbara went to different places. Nobody, not one of them, have returned.” At first they lived on money from the cattle. Eventually, he bought a rustic loom and taught himself how to weave.

In 2003, he began working with fair trade organization Allpa to develop products and fulfill export orders. Today, Celestino has a new workshop where he employs more than 70 weavers.

I feel that I have achieved what I wanted. I can make more things… improving the quality, it is all in our hands… Nothing is difficult, nothing is impossible. I have more knowledge, more creativity than I used to.

Celestino’s story is that of a self-made man who used his determination to learn and used his knowledge to help others. But as incredible as his tale may be, there are many other like him, who have faced huge, life-changing decisions.

Giving up all that is familiar, and taking a risk in the hopes of making a better future for their children. In a country with limited support from the government, people make their own way. And sometimes they take it upon themselves to learn a new skill, and, if they’re determined enough, the risk is worth the reward.

Leave a comment